Written by Kristine Flacké Haualand, PhD candidate at the Bjerknes Centre and the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen. The article was first published on Scisnack.

Between the warm tropics and the cold polar regions exists a broad belt of strong latitudinal temperature contrasts: the midlatitudes. The weather here is dominated by cyclones, associated with wet and windy weather, and anticyclones, associated with calm and sunny weather. Before these weather systems hit land and affect our daily lives and picnic plans, they have often formed and traveled over open ocean, from which they’ve picked up a lot of heat and moisture. Let’s start at the cradle of midlatitude cyclones and see how the ocean influences their intensity before they potentially grow to mature storms and make landfall.

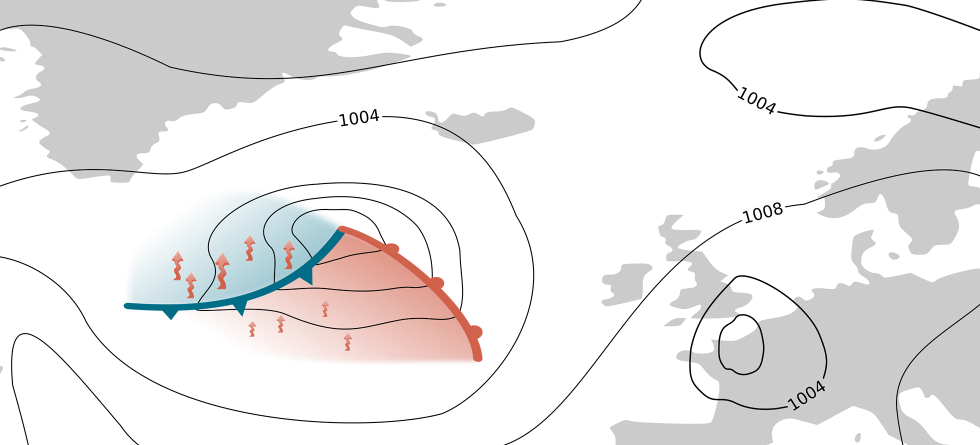

Many baby storms are born along the Gulf Stream, where warm, tropical water flows poleward. With the warm ocean below, the cold sector of the storm gets heated by the ocean such that the horizontal temperature contrast across the storm core weakens. This is sad news for the baby storm because temperature contrasts provide an important energy source for her growth. But someone is happy! Further down the path of the storm sit people like us enjoying the benefits of calmer weather.

While the ocean provides heat that calms down the weather, the ocean also provides moisture to the storms. With more moisture comes more clouds that intensify the storms. The role of the ocean is therefore two-fold, with the heat from the ocean weakening storm development, and the moisture from the ocean intensifying it.

For typical environmental conditions, especially in a warmer climate, the effect of moisture dominates, such that the overall effect of the ocean is storm intensification. Maybe just enough to postpone those picnic plans?

Read about how clouds and rain influence lows here.

Reference

Haualand, K. F., and T. Spengler, 2020: Direct and Indirect Effects of Surface Fluxes on Moist Baroclinic Development in an Idealized Framework. J. Atmos. Sci., 77, 3211–3225, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-19-0328.1.