News

13.01.26

Cities are essential for climate

The majority of the world's population lives in cities. Providing cities with solutions to handle climate change improves both the global environment and local living conditions.

Tags: Global Climate

29.12.25

The Bjerknes Year 2025

A new year stands at the doorstep. While we wait for all things new, lets take a moment to look back at the year that was.

18.12.25

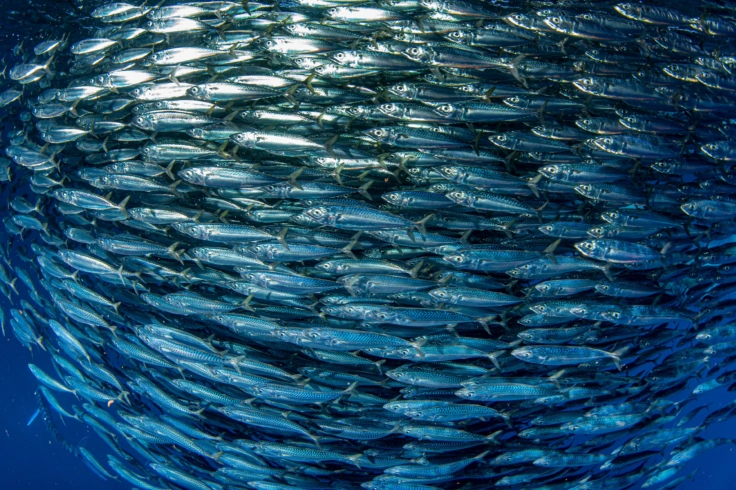

When Pacific Weather Shakes Atlantic Fisheries

How El Niño and La Niña reach across the globe to impact fish populations thousands of kilometres away

09.12.25

The cod has followed the thermometer

In recent decades the cod stock in the Barents Sea has gone up and down with the ocean temperature. Future development depends on more than the water.

Tags: Polar, sea ice, Barents Sea, fish

09.12.25

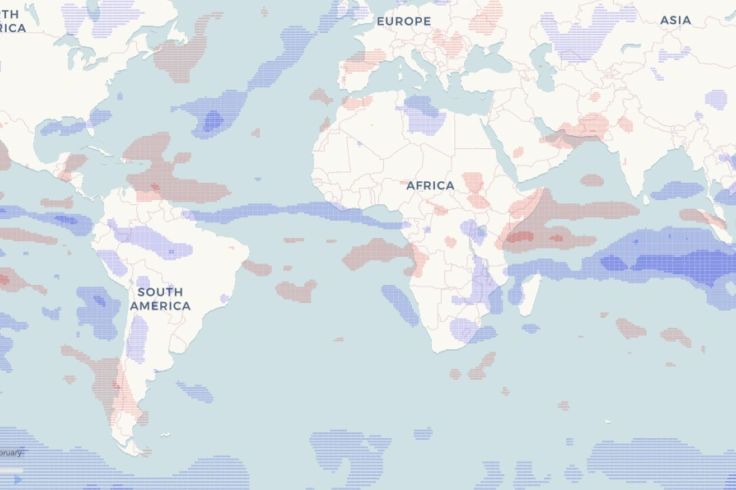

Looking at freshwater in a new way

Freshwater is quietly reshaping the oceans — and with it, the climate. A new study has looked at how rain, river runoff, and melting sea ice spread through the world’s oceans, revealing differences between the Arctic and Antarctic.

25.11.25

All the water we cannot see

Only a fraction of the ocean lies at the surface. How can we find out what happens in water that lies underwater?

13.11.25

Another record year for fossil fuel emissions

Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels are projected to be 1.1 % higher in 2025. The ocean CO₂ uptake was re-evaluated based on stronger evidence and new understanding.

03.11.25

Banned gases reveal the age of water

The use of gases that deplete the ozone layer has been restricted for almost forty years. Still such substances linger in the ocean – a troublesome legacy marine scientists can exploit to keep track of the ocean circulation.

Tags: AMOC

29.10.25

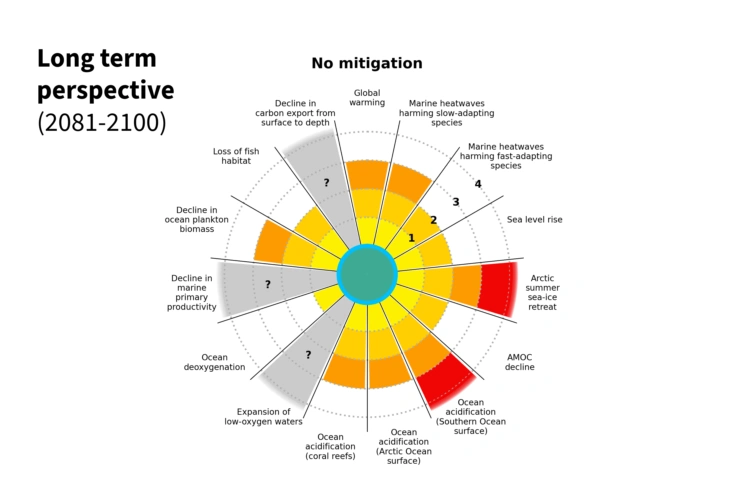

Mapping the comfort zone of ocean life

What is the safe operating space of marine ecosystems? In a new paper, Timothée Bourgeois and colleagues investigate the limits of marine ecosystems to preserve of biodiversity, food security, biodiversity and risk for human societies.

Tags: Carbon

27.10.25

Future climate in Norway: More floods, droughts, and less snow

The climate in Norway has already undergone significant changes, and the effects are set to intensify in the coming years. This is demonstrated by a new report from the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS).

21.10.25

How can we tell temperatures from thousands of years ago?

Sher-Rine Kong has been studying a lake in Svalbard, and her findings suggest that temperatures during the Early Holocene - around 11,700 years ago - were up to 3.5 °C warmer than today. But how can they know what the lake temperature was back then?

13.10.25

Two Systems, One Critical Challenge

The new Global Tipping Point Report is out and warns of potential risks to the Atlantic Ocean Circulation – however, there are large uncertainties about when, or if, the tipping points will be crossed.

30.09.25

Bringing Climate Models to Everyone

How AI is making complex data understandable

18.09.25

Rebekka is the Winner of Forsker Grand Prix Bergen 2025

Congratulations to Rebekka Frøystad, PhD candidate at GEO – and to Nina Hecej who made it to the regional final.

08.09.25

Where do the icebergs drift?

In June, Lars H. Smedsrud, Linda Latuta and Angela Muhmenthaler from UiB and the Bjerknes Centre travelled to Greenland to measure icebergs. Curious how? Take a look at the video.

04.09.25

Blue specks in the white north

On or in the North Pole? Prepositions can be hard, especially when ice turns into water. This week a research expedition reached the North Pole – surprisingly easily.

Tags: Polar, Hazards

21.08.25

"Perfect Storm" under the midnight sun triggered marine heatwave and explosion of salmon lice

On August 5, 2024, a marine heatwave began along the coast of Lofoten in Northern Norway. It lasted for 21 days, with sea temperatures measured at a record high. This caused salmon lice to thrive.

20.08.25

"Why doesn't it rain more?"

Climate change enhances extreme rains more than the ordinary drizzle. New research shows that frontal rain increases the most, and illustrates why extreme rains caused by other phenomena are not equally affected.

Tags: Hazards

11.07.25

Loss of sea ice stabilizes Atlantic circulation

The risk of a slowdown of the overturning circulation in the North Atlantic Ocean is lower than previously thought. New research suggests increased deep water formation in ice-free regions of the Arctic Ocean will keep the wheel spinning.

Tags: Polar, AMOC, sea ice, Gulf Stream, Arctic

03.07.25

Lise Øvreås Elected as New President of EASAC

Lise Øvreås stepped down last year as President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. Now she is taking over as President of EASAC, a coalition of 30 science academies from across Europe.