Dramatic Changes in the Greenland Sea

Due to climate change, deep water production has changed fundamentally in the Northern Hemisphere. This has major consequences for ocean circulation and the ocean's ability to absorb carbon.

Publisert 18. March 2025

Written by Thea Svensson

Photo of ice in the Greenland Sea. Photo: Ellen Viste

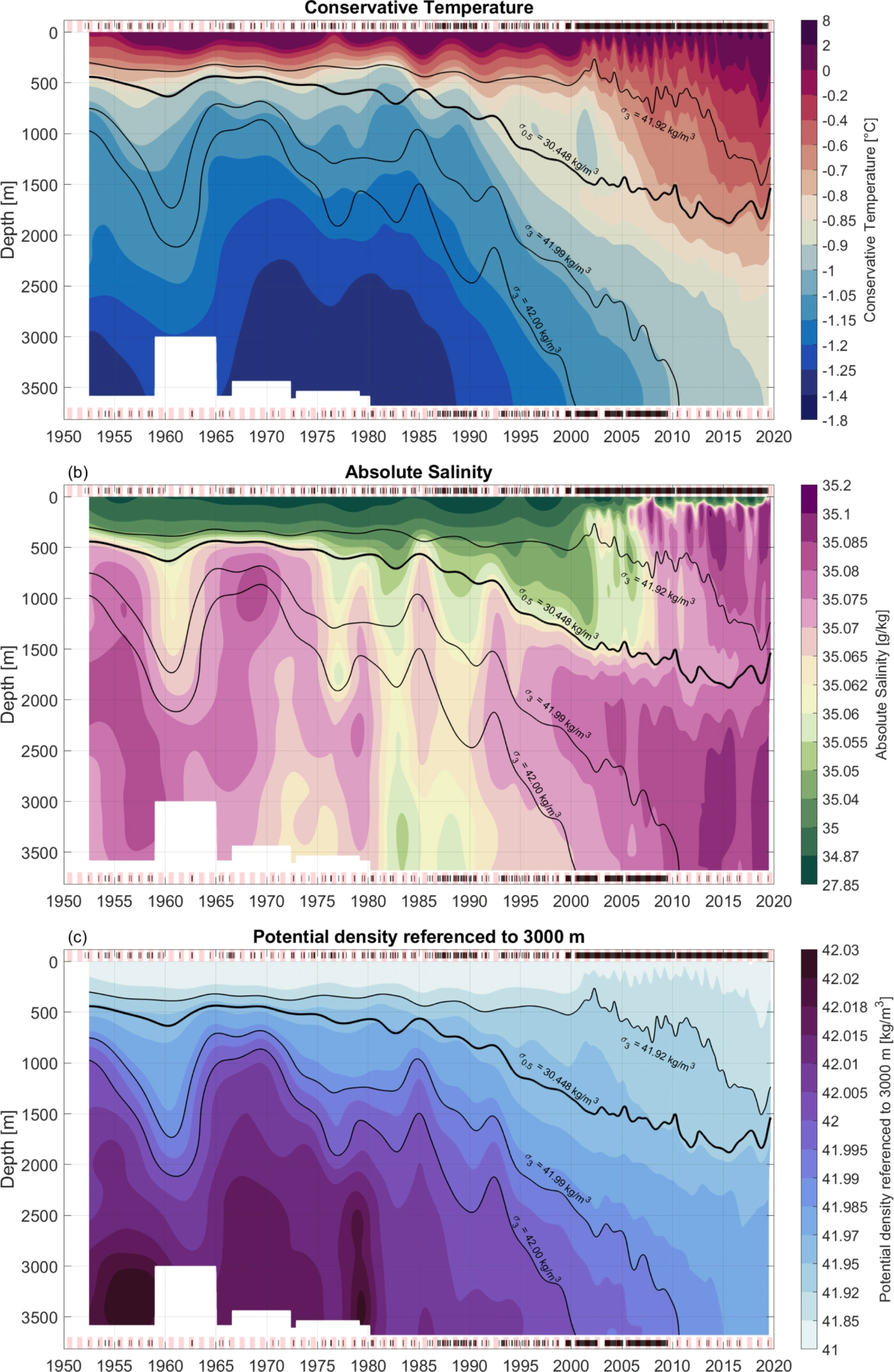

The Greenland Sea has undergone significant changes since the mid-1980s. Previously, this area was known for the production of Greenland Sea Deep Water (GSDW), which is formed through convection and sinks all the way to the ocean floor. This water was the densest in the Nordic and Arctic Seas and covered the seafloor in all deep basins.

Because the water was located so deep, it could not flow over the relatively shallow Greenland-Scotland Ridge, and thus did not contribute to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). However, today the situation has changed dramatically, and the Greenland Sea is now a major contributor to AMOC.

Instead of producing heavy deep water, i.e., water with very high density, the Greenland Sea now produces lighter water—water that is much less dense. This has significant consequences for both ocean circulation and the global climate. The change in water properties has not only affected circulation in the Greenland Sea, but also the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon, as well as potential ecological consequences.

Causes of the Change

Several factors have contributed to this transition. First, increased freshwater input in the 1990s hindered the formation of the dense GSDW. A layer of less dense water settled on top, effectively isolating the GSDW, which is still present at depth, trapped in a basin 3,600 meters below the surface. The Greenland Sea has thus become stratified, with dense GSDW at depth and a new, less dense water mass filling the top 2,000 meters.

At the same time, the ongoing warming of the ocean has further intensified this stratification. Despite an increase in salinity, which also affects the density of water, the warming has maintained a layer of less dense water known as the Greenland Sea Arctic Intermediate Water (GSAIW) above the deeper GSDW layers. In addition to a higher temperature, GSAIW also has a higher salinity than the old GSDW. As a result, the Greenland Sea has transitioned from being a salt-dominated system to a temperature-controlled system.

Development of (a) temperature, (b) salinity, (c) density from 1950 - 2020. Each black line at the top indicates the presence of a profile, and red and white colors represent summer (May–October) and winter (November–April) months, respectively. At the bottom, profiles extending deeper than 2,000 meters are marked.

Major Consequences for the Ocean and Climate

Deep ocean currents is primarily driven by density differences. Changes in density, therefore, have major consequences for both vertical movement (overturning) and horizontal movement (circulation). As a result of the general warming of the ocean, GSAIW is significantly warmer and much less dense than GSDW. The previous GSDW did not contribute to the AMOC, but the new intermediate water is light enough to pass over the Scotland-Greenland ridge, and now contributes to the AMOC.

The change in density has already had several consequences. The most important one is that the water formed in the Greenland Sea no longer reach the deepest layers of the Nordic seas—the local overturning has become much shallower. In other words, there is no longer a renewal of deep water in this area, which may have serious ecological consequences. The oxygen in these deep layers is no longer replenished, and any life in the deep has not received oxygen since the 1980s. Unfortunately, we know little about what lives so deep or what effect the lack of oxygen may have had.

Additionally, the previous production of GSDW led to significant carbon storage in the deep ocean, but this carbon uptake no longer occurs. The processes that once contributed to CO2 storage have ceased, and yet another carbon sink has disappeared from the ocean.

Changes in Convection Patterns

The transition from salt-dominated to temperature-dominated stratification has affected how overturning occurs in the Greenland Sea. Previously, when stratification was salt-dominated, overturning occurred quickly at the end of the winter. This led to deep mixing of water masses. Now, with temperature-controlled stratification, overturning happens more gradually throughout the cooling season. This change has implications for energy and material exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere.

The deep water that previously formed in the Greenland Sea originated under very specific conditions—it was exceptionally cold water, even within the Nordic seas. When cold water reaches a certain depth, known as the thermobaric depth, thermobaric convection occurs, causing the water to sink all the way to the seafloor.

Over the past 30 years, this boundary has shifted 1,000 meters downward, from 1,500 meters to 2,500 meters, making it much more difficult for water to sink. Thermobaric convection has ceased in the Northern Hemisphere and now only occurs in the Southern Ocean, where it is colder.

Implications for Regional and Global Ocean Circulation

The changes in the Greenland Sea have significant implications for both regional and global ocean circulation. First, there has been a redistribution of the sources of overflow water that previously contributed to AMOC.

This may affect the strength and stability of this important overturning. The Greenland Sea still plays a key role in overturning in the Nordic seas, but now through the formation of intermediate water rather than deep water. This change may have consequences for the ocean’s heat transport and climate dynamics.

Future Outlook

Although the major changes that have occurred in the Greenland Sea are significant, research suggests that the region will still play an important role in ocean circulation in a warmer future. The water in the area has low buoyancy content, making it weakly stratified and easier for convection to occur.

There is also slow a buoyancy renewal in the region, which allows water masses to retain their properties over time. The Greenland Sea has become more sensitive to atmospheric cooling, which increases the potential for local water mass transformation.

These factors show that the Greenland Sea will continue to be a key region for ocean circulation, even though the specific processes have changed. It remains important to monitor and understand developments in the Greenland Sea in order to predict how ocean circulation will evolve in the future.

Photo from a research expedition in the Greenland Sea. Photo: Anna-Marie Strehl.

Conclusion

The changes in deep water overturning in the Greenland Sea represent a significant shift in the region’s oceanography. The transition from deep water production to intermediate water production has important consequences for ocean currents and climate dynamics in the North Atlantic.

The Greenland Sea has ceased to function as a major source of deep water, impacting both ocean circulation and the carbon cycle. At the same time, it has become a significant contributor to AMOC, and this change may have far-reaching consequences for the ocean’s heat transport and the global climate. Continued research and monitoring of the area are crucial for understanding the potential consequences of these changes.

Researcher in the Greenland Sea

Anna-Marie Strehl recently received her PhD with the thesis "Long-term changes stratification and convection in the Nordic Seas – an observational perspective". The thesis deals with changes in the Greenland Sea over the past 70 years and is the background for this article. She is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bergen and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, researching water mass transformation at high latitudes and their contribution to the AMOC, as part of the ROVER project.

In ROVER, the researchers will observe water mass transformation in the East Greenland Current, both through a winter expedition on an icebreaker, using moorings over the Greenland Slope and autonomous underwater gliders. The measurement campaign will provide groundbreaking data, crucial for understanding the processes that deliver cold, deep dense water to the lower part of the AMOC.

References

Anna-Marie Strehl, Kjetil Våge, etal. "A 70-year perspective on water-mass transformation in the Greenland Sea: From thermobaric to thermal convection", Progress in Oceanography, Volume 227, 2024, 103304, ISSN 0079-6611,

Related Projects

Resilient northern overturning in a warming climate

In ROVER the researchers will observe the deep-water formation along east Greenland, both through a winter expedition on an icebreaker, using mooring across the Greenland slope, and autonomous underwater gliders. The measurement campaign will provide groundbreaking data, cruical for the understanding of the processes that supply cold, deep water to the lower limb of the AMOC.