This article was first published in the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten 31 December 2015.

We heard about it on the radio, and we saw it on TV. Dry sand, arid fields, animals and people who had too little water and too little food. In the 1970s and ’80s, one drought year followed another, both in the Horn of Africa and in the Sahel, the semi-dry belt between the dry Sahara and the wet tropics farther south.

It was one of the greatest climate shifts that have been observed. The ’50s and ’60s had been wet, while in the ’70s and ’80s it got steadily drier. It seemed as if the Sahara were marching south.

It was because of humans, we were told. People had strained the soil by cutting down bushes and trees for firewood and by having too many grazing animals. Now the sand dunes threatened to engulf the savannah. The theory had its scientific basis in a study from 1975, which showed that a lack of vegetation could create, worsen or prolong drought. But this also gave us hope. If we could get the plants to grow again, they would not only hold onto more of the water that fell and keep the sand away, they might also make it rain more.

There was only one thing to do: We had to plant trees.

The kids step forward

The idea was, according to the National Broadcasting Corporation children’s radio program Barnetimen, extremely simple. Those of us listening to the program would go out and pick spruce cones and send the cones to the radio station. They would have the seeds taken out of the cones and send these seeds back to us, so that we could sow them in milk boxes. When the tiny spruce trees had grown to a few centimeters, we would send the milk box – with soil and plant – to a plant school in the south of Norway. There, they would grow Christmas trees. And those Christmas trees would be sold to pay for planting trees in Mali and Mauretania. Together we would stop the desert.

But the theory about the trees and the rain already had competition. From the ocean.

Rain from distant seas

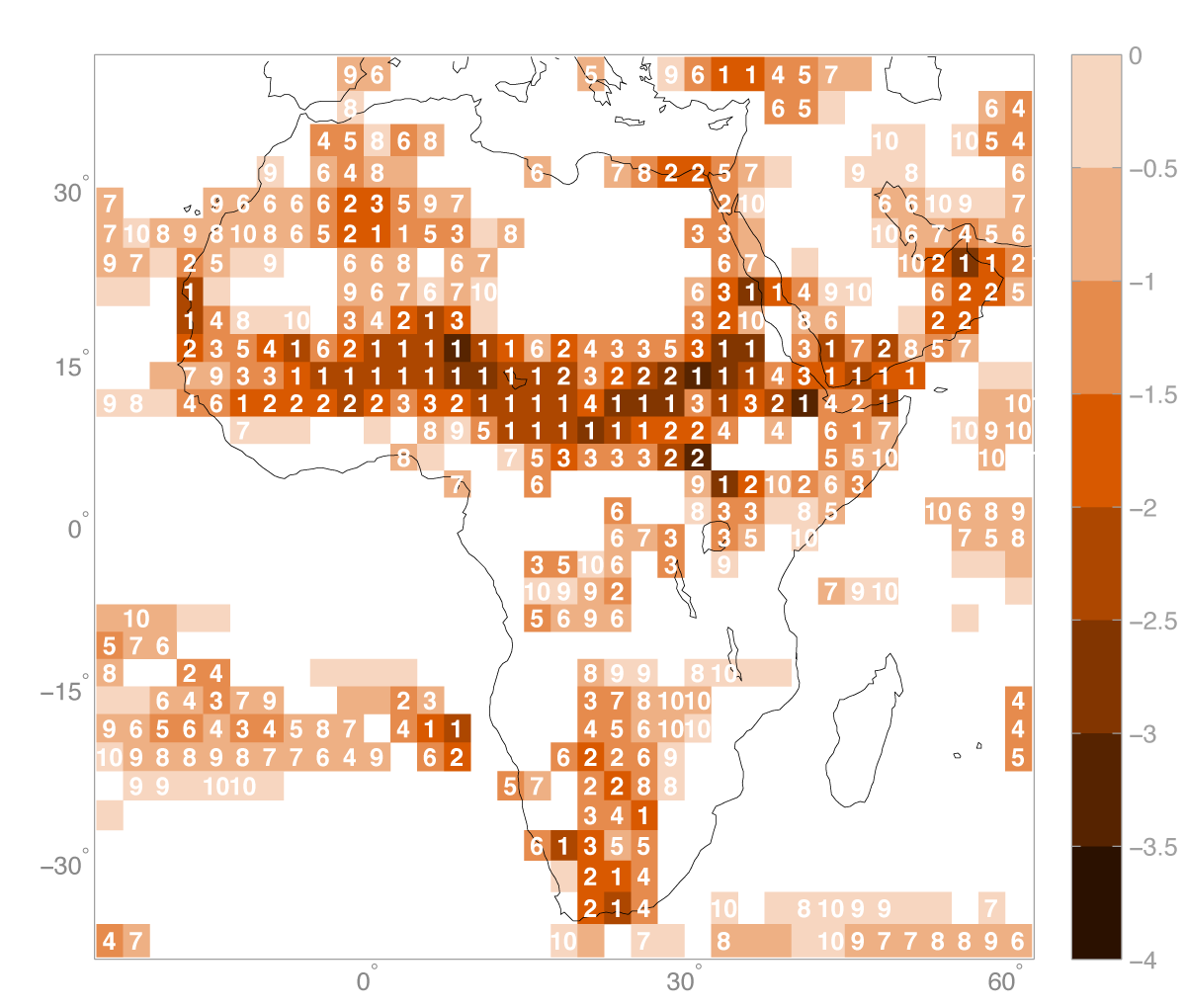

As early as the mid 1980s, British scientists had managed to recreate the precipitation changes in the Sahel in a climate model, based only on the difference between global sea surface temperatures in wet years and dry years. They didn’t need to know anything about the grass in Mali to recreate the shift from wet to dry; all they needed was the temperature in distant ocean regions.

Research in the following years has convinced most people: The 20th century precipitation changes in the Sahel were mainly driven by the sea surface temperature in tropical parts of the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Wave signals in the air

The Pacific is the wild child of the world ocean. In El Niño years, when large areas of the Pacific are warmer than normal, the weather wreaks havoc on many parts of the world. The warm ocean triggers towering clouds and heavy rain, and this generates waves in the air – waves that affect the weather both within and away from the tropics. El Niño is associated with less rain than normal in most of these regions, including the Sahel.

El Niño creates huge differences in rainfall from year to year, but is not to blame for the shift from wet decades to the droughts of the 1970s and ’80s. The shift was probably connected to a general warming of the tropical oceans: in the Pacific, and especially in the Indian Ocean. But the effect is similar to that of El Niño, with torrential rain over the ocean and stable, dry air over land.

The Atlantic was not innocent, either. The rains follow the warmest ocean surface, and temperatures have increased more over southern parts of the tropical Atlantic than farther north. This may have hindered the tropical rain belt from moving far enough north to bring rain over the Sahel.

A need for trees

Still, something was missing. Only ocean temperatures were needed to recreate the change from wet decades to drought in the climate models. The models were spot on in time as well as location. But they were not able to make the drought as severe as it had actually been. That’s where the trees come in.

Without grass, bushes and trees, more of the radiation coming from the sun to the earth is reflected back into the atmosphere. Thus, the ground does not warm up as much, and doesn’t heat the air above as much, the air then doesn’t rise as quickly, fewer clouds form, and there is less rain. The humidity of the soil also influences the rain. These effects are not large, but they do contribute to drier conditions.

That the temperature of the oceans governs the development in the Sahel, does not mean that the conditions on the ground are inconsequential. But it does mean that their role is different from what we first thought. Local plants can enhance the drought that the distant oceans instigated.

Connections fall apart

In the 1990s, it began to rain more again. Not as much as in the ’50s and ’60s, but more than in the dry decades of the ’70s and ’80s. Had the Indian Ocean cooled? No, quite the opposite, the Indian Ocean continues to get warmer and warmer. The simple relationship from the past is no longer there, not now and probably not in the future.

Climate models do not agree on what will happen in the Sahel over the coming century. While some are locked in a dry climate, others predict increased rainfall. Researchers at the German Max Planck institute have shown that the answer once again may lie in the ocean. While higher temperatures in the tropical Atlantic produces less rain in the Sahel, a warming of the ocean farther north favors more rain. The final result depends on where the warming will be the greatest, and that is where the models disagree.

In the 20th century, the temperature of the tropical oceans governed the Sahel. Juergen Bader, who in addition to Max Planck is affiliated with the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, believes this was because temperature variations in the ocean farther north were too small to play any role. The link between ocean temperatures and rainfall in the Sahel is by no means gone, but in the future, it may be the influence of the regions to the north that dominate, and no longer the tropics.

Thus, we humans may still have a part in steering Sahelian rainfall. Not the local farmers gathering firewood, but the world outside. The ocean has caused shifts from wet to dry to wetter again, but what caused the changes in the ocean? In addition to natural oscillations, anthropogenic emissions of both aerosols and greenhouse gases may have played a role.

Success in Norway

I never picked spruce cones for the Sahel. I was a passive listener who ran to the radio to learn about exotic countries, but who never planted Christmas trees. I wish I had.

In Norway, the children’s campaign Stopp ørkenen (Stop the desert) was a huge success. More than 15,000 kids sowed spruce seeds, the royal family sowed seeds, retirees volunteered to pack seeds, Elton John came to perform at a charity concert, and our own singer Jahn Teigen and former European boxing champion Steffen Tangstad sold shares in support of the case. King Olav bought the first share. The children’s radio program was broadcast from the Ministry of the Environment, where two ministers sang the program’s theme song while the minister of transportation accompanied on the clarinet. There are press photos of prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland sowing spruce seeds in a milk box. Everyone contributed.

For Mali and Mauretania, it hardly mattered. The few trees that were planted there, quickly died. And if it they had lived, it is very unlikely that they would have been able to win over the influence from the global oceans.

It’s easy to laugh at the good intentions of the 1980s, both the scientific ones, and those that involved sending around spruce cones and milk boxes by mail. But it’s completely natural that scientific theories evolve. And the kids who went out to pick spruce cones must have felt that they took part in creating a better world. I wish I could say I had been one of them.

Sources

Charney, 1975: Dynamics of deserts and drought in the Sahel. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society.

Park, et al., 2015: Northern-hemispheric differential warming is the key to understanding the discrepancies in the projected Sahel rainfall. Nature Communications.

Rodriguez-Fonseca et al., 2015: Variability and Predictability of West African Droughts: A Review on the Role of Sea Surface Temperature Anomalies. Journal of Climate.

News articles from NRK (The Norwegian National Broadcasting Corporation), NTB (The Norwegian News Agency) and the newspaper Aftenposten in 1988–89.