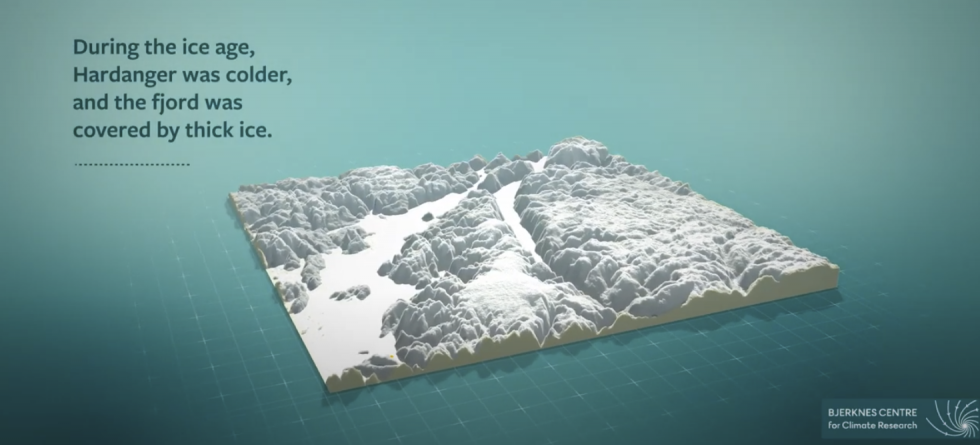

The Hardanger region in southwestern Norway is famous for a mild climate, steep rock walls and delicious apples. Towards the end of the last ice age, things were different. Climate was frigid, too cold for humans to settle, let alone apple trees. The Hardangerfjord Glacier reached from the Hardangervidda plateau in the east, towards the island Halsnøy towards the west. These gravelly islands were themselves created a few centuries earlier, by the bulldozing force of the glacier. This Norwegian ice-age landscape reminds us of the coasts of Greenland, with impressive fjords hosting glaciers and icebergs.

A new study reveals how climate warming at the end of the last ice age caused the great glacier covering Hardanger to collapse around 11.000 years ago. The study is done by a team of scientists from the University of Bergen, the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, the University of Svalbard, Stockholm University, and the Bolin Centre for Climate Research. The findings are now published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Among the fastest glacier retreats worldwide

During the ice age, a large cold blanket of ice covered the British Isles, Scandinavia and parts of Russia. Norway was covered by kilometres of ice, including the Hardangerfjord. As climate warmed, the glacier in the fjord started to melt and retreat fast.

"When the ice age was over, things got quite dramatic. Temperatures rose several degrees in a matter of decades. The retreat of the Hardangerfjord Glacier was incredibly quick, actually one of the fastest lasting meltdowns of a glacier that we know of," says Henning Åkesson, who has lead the study.

Åkesson is a post-doctoral researcher at Stockholm University, previously at the University of Bergen and the Bjerknes Centre. The study gives new insights into how the Hardangerfjord Glacier vanished, and is the result of a close collaboration between glaciologists, geologists and climate scientists.

Through computer simulations, the scientists have reconstructed a detailed picture of the rapid melting. The glacier reacted strongly to the climate warming when the last ice age ended, and retreated 125 km over a period of 500 years, giving a mean long-term retreat rate of 250 metres per year. The retreat was a combination of melting at the surface and by the warming fjord waters, and iceberg calving.

This is similar to what is measured in the fjords of Greenland today, as a result of global warming.

The submarine landscape controls the speed

"When temperatures rise, glaciers melt. This is obvious, but the pace of retreat can vary greatly. We find that the landscape of the seafloor is the the deciding factor," says Åkesson.

He points at an example close to the fjord-side village of Jondal, where the fjord is nearly 900 m deep.

Further towards the coast, between the villages of Rosendal and Jondal, the retreat was slow. Along this part of the fjord, the fjord bottom shoals moving inland, until we reach a fjord sill at 500 metres depth. Such sills are known to slow down the retreat of fjord glaciers. A melting glacier can be left hanging several decades on such “submarine hills” at the fjord floor, even though the known climate warming indicates that the glacier would continue to retreat quickly.

"In such settings, we may easily be misled and think that the retreat has stopped, while in reality, it is just a short breather for the glacier. Therefore we really need to know what the submarine landscape looks like," Åkesson points out.

Over the submarine hills

As a glacier loses its grip at a sill, things literally go downhill.

The study of Hardangerfjorden is a great example of this. From the sill, the fjord floor plunges “downhill” for almost 30 kilometres, before getting gradually shallower towards the village Eidfjord at the fjord head.

The scientists show that during the most dramatic period, the glacier retreated 10 meters per day, or several kilometres every year.

"If you were using the local ferry to Jondal at this time, you could have witnessed the glacier melting back with your own eyes," Åkesson says.

Clues from the past

The simulation of the collapse of Hardangerfjord Glacier gives clues about the impact of climate change on glaciers today, according to Åkesson, for example in Greenland.

A temperature rise similar to that at the end of the ice age, will occur in the near future due to global warming, unless man-made emissions of greenhouse gases are drastically reduced. Such climate warming is critical in deciding the fate of the ice on Greenland and in the fjords around the continent.

Scientists have long been troubled about the health of the Greenland Ice Sheet, where many glaciers have started to flow faster and have retreated many kilometres over the last 20 years.

Ice melt in Greenland is of great consequence for the coastal landscape, wildlife and the local people, while also adding to an already steadily rising global sea level. In the long-run, the entire ice sheet on Greenland is in danger. In the worst-case scenario, the ice sheet will melt away, causing global sea level to rise with seven metres, though this is not expected in at least another 1000 years from now.

Reference:

Henning Åkesson, Richard Gyllencreutz, Jan Mangerud, John Inge Svendsen, Faezeh M. Nick, Kerim H. Nisancioglu,

Rapid retreat of a Scandinavian marine outlet glacier in response to warming at the last glacial termination, Quaternary Science Reviews,

Volume 250, 2020, 106645, ISSN 0277-3791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106645