This article was first published at Energi og klima / To grader (in Norwegian) 10 December 2014.

Increased knowledge of historical changes in climate has created a completely new phenomenon: A permanent uncertainty of how water will flow in the future. When the water takes new ways, the power balance also changes, says Terje Tvedt.

For years, Tvedt has studied historical changes in the relationship between water and society. The professor has a series of scientific works and books about water behind him, and is known to a wider audience through several TV documentaries – latest the series “The Nile Quest”.

Between two intense fall showers I met Tvedt at St. Hanshaugen in Oslo, for a conversation about water and climate, relations of power, and research.

“We live in the ‘time of water insecurity’”, argues Tvedt. “No matter where you go in the world, no matter who you meet, in discussions about the weather, people immediately point to global warming as the cause.“

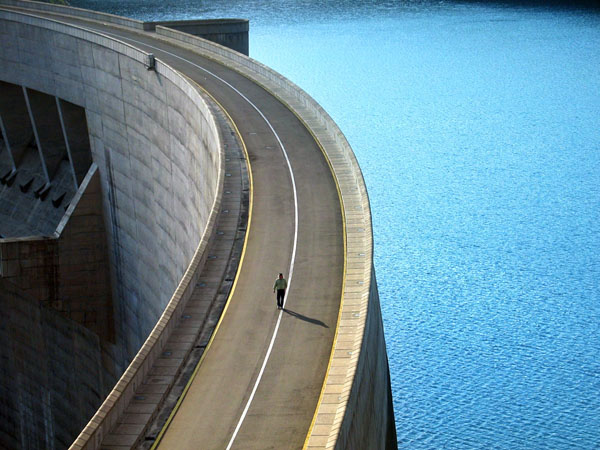

“A hundred years ago you could plan large hydropower plants without asking whether the discharge of the rivers would change in the long run. Now, no hydro-engineer anywhere would plan a large construction without considering the possible consequences of climatic changes,” says Tvedt.

The main reason for the uncertainty about the future is, paradoxically, new research about the past.

“New knowledge about the climate and how quickly and how frequently it has changed through history, means that people who act as if it will remain stable, are suddenly perceived as stupid or naïve,” he says.

With knowledge, in this case of how the future may evolve, follows power.

“The power of definition over the future water landscape is power almost without limitations. Even the most powerful popes have had to share their power with God. The climate scientist can point to science and say that “this is what it’s going to be like”. And if you win that power of definition, many people will dance to your pipe.”

How society should follow up on results from the climate sciences, becomes a central field of debate.

“A whole new figure of thought has conquered a central position in society for good, and we do not yet know the consequences. It’s only in a long-term perspective that the radical about this new time of water insecurity can be understood”, says Tvedt.

Complex conflicts

Tvedt articulates it like this: Future changes in climate will in society first and foremost be expressed as changes in the way the water flows, as the consequences of what he calls the hydrological and hydrosocial circle. That such changes will create conflict is easy to imagine. Perhaps too easy. I originally planned to ask for help to make a list of the world’s most important conflicts about water resources where climate change is a factor. Likely, in the back of my head I had one of those catchy lists of “the five most important this and that” that the Internet is submerged by. But Tvedt protests. He warns against using climate change as an explanation for complex conflicts. Such simplifications may strike back.

“One picks out popular and gripping examples that do not hold true, and thus in the long run undermines the graveness of climate change.“

The war in Darfur in the Sudan is one such example, Tvedt thinks.

“A lot of people said that the war in Darfur must be understood as a result of climate change – that the water disappeared and the wells were gone, etc., and thus the war started. This is pure rubbish. There is no empirical evidence for it. The conflict had a completely different background with deeper roots. Changes in the environment was of course one of many factors, but if you reduce that conflict to a question of changes in the water in Darfur, then you reduce the complexity of society so radically that you cannot possibly understand what’s going on.”

This does not mean that there are no conflicts where climate is an important factor – not the least conflicts based on the fear of future climate changes. One of Tvedt’s examples is the Netherlands.

“The government said that now we have to stop building dikes, because we can’t build dikes to heaven if there is more and more water in the rivers. Instead they decided to give land back to the water. This means that some of the farmers that have established farms have to stop farming and move to the city. This means that there is a conflict between farmers and government, because the Dutch government thinks that the discharge in the rivers will increase and already has increased.”

The most interesting aspect with the water question rising steadily on the political agenda, is not that it will lead to war and conflict, as many people talk about, but how it will affect the distribution and use of power in society, thinks Tvedt. What kind of power do you have if you have control over water sources in a region where many people want that water?

The Middle water kingdom

Discussions about climate sooner or later leads to China – the country that more than any other country will determine how well the world will manage to handle climate change. There are few places in the world where the consciousness of the power of climate is as great as in China, Tvedt points out. Chinese historians have found relationships between the rise and fall of dynasties and changes in the climate. One of the things that strongly diminished the last empire was dramatic changes in the climate at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. The changes made the hydrological system collapse, the intricate water transport system the Chinese had developed failed them, and the dynasty did not manage to retain power.

“In China, the attention about the relationship between political power and the monsoon’s way of watering the land is pretty strong”, says Tvedt.

The leaders naturally also know that the monsoon is influenced by changes in winds, ocean currents and temperatures, and the hydrological cycle. The Chinese leadership is part of a long-standing culture characterized by strategic thinking, Tvedt points out. They struggle with getting control over emissions and gigantic environmental problems in a complex and quickly growing coal-based economy, but that does not mean that climate change does not worry them.

“I think we underestimate the Chinese leadership’s concern with the sustainability of the state, if we believe it is because they do not think about it, that they do not do more than they do.”

In China, the more than 2000 year old Emperor’s Canal (Grand Canal) is still in use. Those in power today have started their own gigantic canal project to solve China’s water problems. With the country’s fast economic growth, the need for water has increased enormously. Via several canals, water will be transported from the south, which is rich in water, to the dry north. Parts of the project have already been completed.

Through Tibet, China controls an area that will be one of the most central strategic areas in the world, Tvedt writes in the book “Vann – reiser i vannets fortid og fremtid” (in Norwegian). The ice stored in 15 000 Himalayan glaciers is the water bank of Asia. The enormous consequences it would have if the glaciers melted, provides China with yet another strong incentive for action against climate change. Control over water resources that are vital to several neighboring countries also gives China power in the region.

“It’s clear that the Chinese, like many others, see the potential power in controlling other countries’ water. They know they are upstream of India, many of India’s most important rivers, and the same for Bangladesh and many of the Southeast Asian countries along the Mekong River. But if they might want to use this as a direct means of power, and when and in which way, is totally uncertain. But they know they have the possibility, and the others know it as well”, says Tvedt.

New water, new power

The debates about water and climate have a tendency to focus on crisis scenarios, like the increased risk of drought or frequent flooding. But the regional variations are large, and all news are not bad news. One example is the fairly recently discovered Guaraní ground water reservoir in South America. This reservoir contains 37,000 cubic kilometers of water, enough for the whole world to drink in 200 years. In a climate perspective, the interesting thing about such discoveries is that they can function as a “water bank” for a long time, Tvedt remarks.

“To the degree that you find such lakes of water under the ground, whether it is at the sea bed or in other places, those countries that find them will have a resource of water that makes them less vulnerable to changes in the climate than societies without such banks of water.”

Desalination of seawater – by itself no new invention – is another possible solution to regional water crises. Near San Diego in California, one of the largest desalination plants in the world is being constructed, projected to be finished in 2016. California hopes that desalination will be an important contribution in the struggle against the chronic scarcity of water in the state. However, desalination creates pollution and other environmental problems, among others when removing the extracted salt. If these problems are solved, and the costs lowered, large-scale desalination may also affect power relations, says Tvedt.

“Just think of what it will mean for global and national migration that areas close to the ocean will have solved their freshwater problem. If water scarcity increases in other areas, this will mean that more and more people will head for the coast. Movement from the inland to the coast, which has been very radical the last 100 years, will speed up even more.“

More economical use of the water, for instance in irrigation, and measures such as reusing as much of the water as possible, can also contribute to mitigate the scarcity of water.

“My point is not that there is a general, global scarcity of water. But the way water flows on the globe is very unfair, and changes in the way water is accessed will create new inequalities”, says Tvedt.

Not in the same boat

In the 1970s, before concerns over global warming, it was suggested to spread ashes over the Greenland ice cap to make it melt faster. The idea was to exploit Greenland’s enormous potential for hydropower and perhaps also find valuable minerals under the ice.

This specific plan was put in the drawer, but Tvedt’s point is that people in different places are affected by climate change in unequal ways. What would seem like wealth and development to the people of Greenland would look quite different for residents of low-lying islands. This makes it difficult to picture humanity unite in a huge common effort against global warming.

“It is extremely naïve to claim that in this case, everybody will be in the same boat. Based on experience from history, it is impossible to state such a thing. And since the climate and the water landscape varies so much geographically, the changes will naturally also be perceived very differently in different places. This also means that one underestimates all the work required to reach agreement about CO2 reductions”, says Tvedt.