Heat waves are associated with sweltering streets and scorched soil. But as likely as humans and cattle, the victims can be corals or fish. Abnormally hot periods also occur in the ocean.

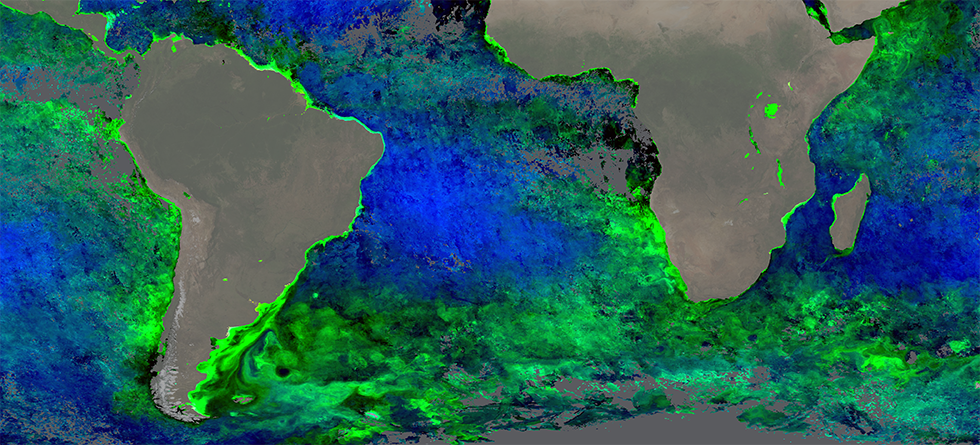

When marine heat waves co-occur with strong acidification and low biological productivity, living conditions in the water deteriorate even further.

“Over the past two decades, the frequency and intensity of these compound events have increased dramatically in the Tropical and South Atlantic,” says Regina Rodrigues, associate professor at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Rodrigues was recently in Bergen to present her work at the fifth International Symposium on Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Oceans.

Since 2014 compound events of marine heat waves, high acidification and little chlorophyll have occurred practically every year in several biologically important regions in the Tropical and South Atlantic. Regina Rodrigues expresses her worry that the recurring events make it harder for life in the ocean to cope.

“This puts in check the capability of the marine ecosystems to recover from these compound extremes,” she says.

A need for monitoring below the surface

Jerry Tjiputra, researcher at NORCE and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, calls for a long-term monitoring system in key vulnerable regions such as the Southern Ocean and the Tropical and North Atlantic.

Tjiputra has used Earth system models to estimate when anthropogenic signals in the global ocean may be detectable under different climate change scenarios.

While changes in surface water are more easily recognized, his work indicates the need for a closer look at greater depths.

“Changes in temperature, salinity, oxygen and pH can occur earlier in the interior ocean than on the surface”, he says. “Below the surface, where most marine organisms live, anthropogenic signals may already have manifested and are potentially predictable.”

Local action to address global targets

“Local actions can mitigate the negative extremes once we have a good monitoring and prediction system,” says Regina Rodrigues.

In the South Atlantic the Agulhas Leakage or Benguela Current region off the coast of Africa has suffered specifically from compound events.

Lynne Shannon, a research professor from the University of Cape Town, has used the South African marine system as a case study to identify local science-policy actions that would address globally relevant targets.

“Interlinking climate and biodiversity targets remains a challenge,” she says.

An array of South African research activities as well as policy and management measures, strive to address both the climate and biodiversity crises. The activities also address outcomes aimed for in the UN Ocean Decade, namely oceans and coasts that are clean, healthy and resilient, predicted, safe, sustainably harvested and productive, transparent and resilient.

Shannon notes that most of the activities have a strong societal component.

“The challenge worldwide will be to ensure that each of our well formulated research, policy and management activities are actually put into action in our governance system”, she says.