Riding the storm

A large-scale flight campaign on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean aims to uncover why some extratropical cyclones develop into storms, while others fizzle out.

Publisert 16. February 2026

Written by Ellen Viste

In the coming weeks low pressure systems approaching Europe from the Atlantic Ocean will be met by three research aircrafts. The aim is to find out what makes some lows particularly strong. Photo: Harald Sodemann

Instruments on the ground show what happens when weather strikes, and satellites see the clouds from above. But, if you want to know what goes on inside a developing cyclone, you have to enter the storm. Over the next weeks, researchers from ten countries gather at an Irish airport to fly in bad weather.

Low pressure centers are formed above the Atlantic Ocean and steered by the wind toward Europe. Their journey can be a few thousand kilometers long and take several days, enough for some of them to develop into powerful storms.

During the ongoing measurement campaign, an American research plane will head for the clouds on the western side of the ocean, where extratropical cyclones form. When the same lows approach land on the eastern side, they will be met by three planes from the base in Ireland. All the aircrafts are loaded with instruments measuring the air and clouds outside.

Setting the stage for the next storm

Rising air is the cause of the clouds and rain associated with weather systems. As air ascends, it cools, and water vapor in the air turns into ice crystals or water droplets. But, this time rising air is not the scientists' main interest.

"The aim is to understand how air sinks before rising in a storm," says Harald Sodemann, professor of meteorology at the Bjerknes Centre and the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen.

"This sinking air sets the stage for new cyclones following the first. Also, some of the strongest gusts are caused by sinking," he continues.

Harald Sodemann has participated in many measurement campaigns using aircrafts to study weather, among other places in Kiruna, on Tenerife, over the Alps, on Greenland, in Alaska and on Corsica. Photo: Ellen Viste

Flying at all levels

Sodemann leads the Norwegian contribution to the operation, which has been under preparation for a decade. While it goes on, around a hundred persons – pilots, mechanics and meteorologists – will be gathered at Shannon International Airport near Limerick.

Three airplanes are ready to take off when cyclones approach over the Atlantic Ocean.

A German airplane will circle above the lows, at an altitude of ten thousand meters, common for commercial flights. Instruments directed downward will provide a bird's eye view of the weather. A smaller, German plane will fly low and see the storms from below.

Between the two, a French airplane will steer into and out of the clouds, with instruments directed both upward and downward. Together the three planes will register what goes on in all parts of the cyclone.

Having collaborated with French researchers for many years, Harald Sodemann has had the opportunity to install one of his instruments in the French aircraft participating in the campaign. In total, 48 institutions in 10 countries are involved. Photo: Harald Sodemann

Sinking air picks up speed from altitudes of several thousand meters

Extratropical cyclones are followed by warm fronts and cold fronts, which are boundaries between warm and cold air.

On weather charts fronts are drawn as red and blue curves, in reality being surfaces continuing upward into the atmosphere. At the fronts warm and moist air slides up over colder air, causing clouds and rain.

While mild and moist air is driven northward ahead of the cold front, air sinks from altitudes of five to six thousand meters behind the front. Because this air is dry and maintains a high speed, strong evaporation occurs as it gets in contact with the sea surface.

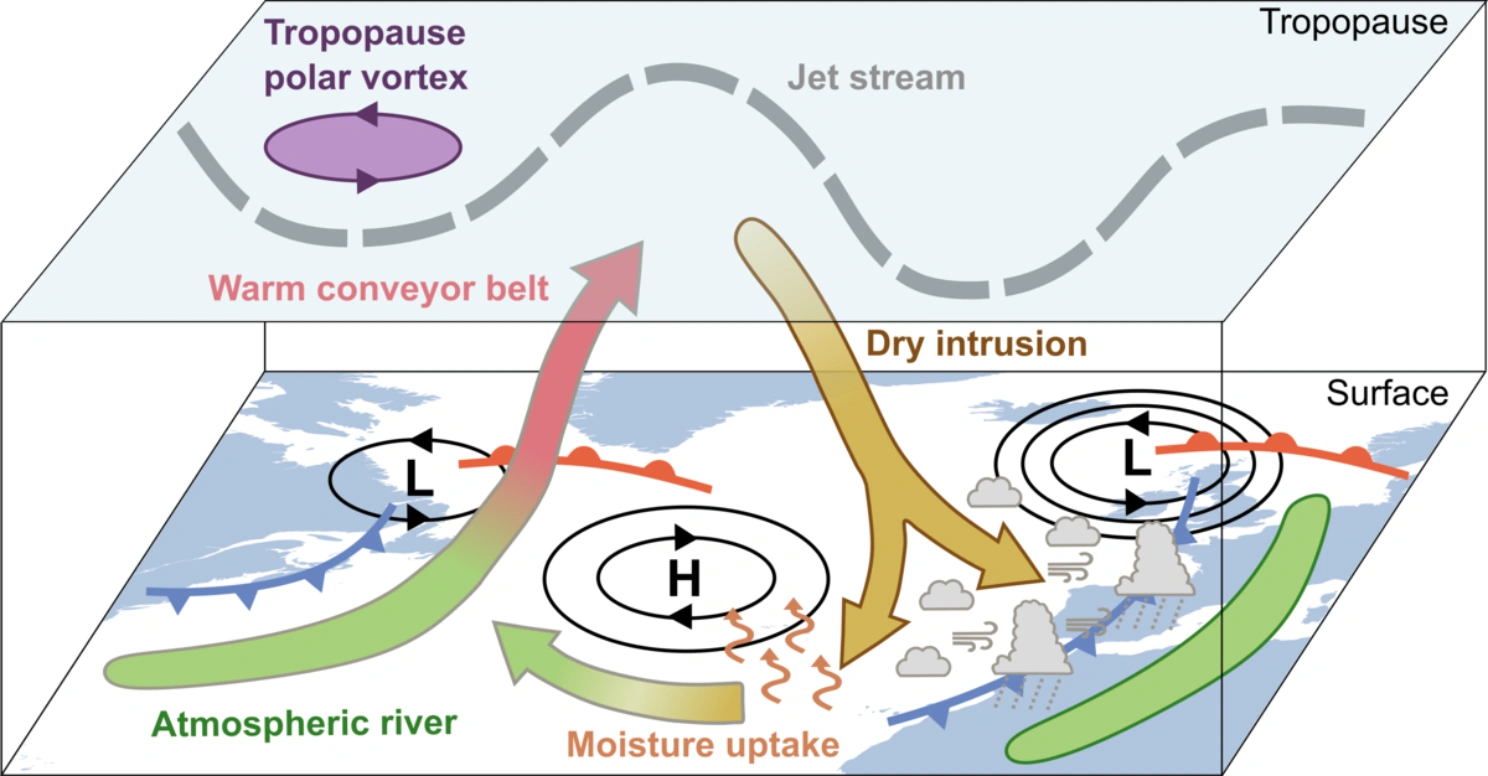

Rising air is an important characteristic of low pressure systems and fronts. Yet, behind the cold front, dry air sinks. When the sinking air reaches the surface of the ocean, it takes up large amounts of water vapor and becomes extremely unstable. Together with strong winds, this contributes to rough weather, there and then as well as in new weather systems succeeding the original cyclone. Image credit: NAWDIC

Water vapor from the ocean makes the air moist, warm and light, almost explosively unstable. It ascends abruptly in convective clouds. The air is messed up far above, contributing to new storms.

Several thousand meters above the ground, wind speeds are high, and the sinking air maintains some of its momentum. Together with other factors this contributes to a phenomenon called a sting jet, with stronger gusts than any other extratropical phenomenon.

Inside the aircrafts, all instruments are attached to sturdy racks. The researchers can follow the measurements on a screen. Harald Sodemann and Sophie Bounissou are ready to go. Photo: Benoît Cellou

Water vapor makes the air traceable

"This is the first time the interaction between rising and sinking air is studied in such an aircraft campaign," says Harald Sodemann.

Norway does not have her own atmospheric research aircraft, but one of Sodemann's instruments has been installed in the French plane, operated by the French national meteorological institute (Météo-France), the French national centre for scientific research (CNRS) and the French national space agency.

While the airplane flies into and out of the clouds, air is sucked from outside the fuselage into Sodemann's instrument. Inside the instrument an infrared laser records water isotopes – different variants of water molecules in the air.

Some water isotopes are heavy, others lighter, and the distribution between heavy and light isotopes can reveal how the air has taken up moisture from the ocean and subsequently released water to form clouds and rain. The isotopes also allow the researchers to trace the air backward in time and find out which regions it has traveled through.

This instrument registers water isotopes in air drawn from outside the hull through the black hose. The image shows the set-up before other instruments were added to the rack. Photo: Harald Sodemann

In need of bad weather

Personnel have been present at the airport in Ireland since the end of January to prepare planes and instruments for take-off. Harald Sodemann admits he is becoming nervous.

"A million things can go wrong," he ways. "We prepare for a thousand alternatives, and the problem will be number one thousand and one."

His main concern is the weather. To find out how rough weather works, they need low pressure systems, preferably long chains of cyclones.

"A large, blocking high over Ireland would be killing," storm chaser Sodemann says.

The long-range forecasts look promising. The high pressure regions seem to stay put over the Norwegian Sea and Scandinavia, while lows steer toward the British Isles and Central Europe. This winter's dominant pattern, bad for the ski season in Western Norway, is good for those who wish to fly in storms over the Atlantic Ocean.

"The mood is good in Ireland now," says Harald Sodemann.

Before leaving Bergen Harald Sodemann was excited to see how European weather would develop in February and March. Photo: Ellen Viste

References

NAWDIC