Fakta

Land heatwaves

The Earth is getting warmer, and news of new heat records appears regularly. When we read about unusually high summer temperatures, it is easy to assume this refers to heatwaves—but that is not always the case. Increased temperatures and heatwaves are not the same thing. So, what exactly is a heatwave?

Oppdatert 23. January 2026

Land heatwaves

- Heatwaves form when persistent atmospheric high‑pressure systems develop during summer.

- These prolonged periods of extreme temperatures are often linked to unusually stable high‑pressure systems, also known as atmospheric blocking.

- A heatwave typically lasts as long as the high‑pressure system remains in place—usually around one week, sometimes up to two.

- Low soil moisture and limited vegetation can intensify heatwaves.

- Heatwaves can develop in both humid and dry climates.

What is considered a heatwave?

A heatwave is a period of abnormally high temperatures relative to a 30‑year reference average. What qualifies as “abnormally high” varies by region and season. For example, a week of 15°C in January in Troms, Norway, would be unusual, but not everyone would consider it a heatwave. In some regions, heatwaves are defined using fixed temperature thresholds - such as 35°C - while in others, temperatures above 35°C may be completely normal.

To quantify abnormal warmth, meteorologists often use a threshold percentile based on historical temperature records. For example, June may be described as experiencing a heatwave if temperatures exceed the top 10 percent of measured June temperatures from a selected 30‑year period for at least five consecutive days.

Because local climate conditions vary widely, so does the definition of a heatwave. In practice, the term is most useful when communicating health risks, helping people prepare and take protective measures.

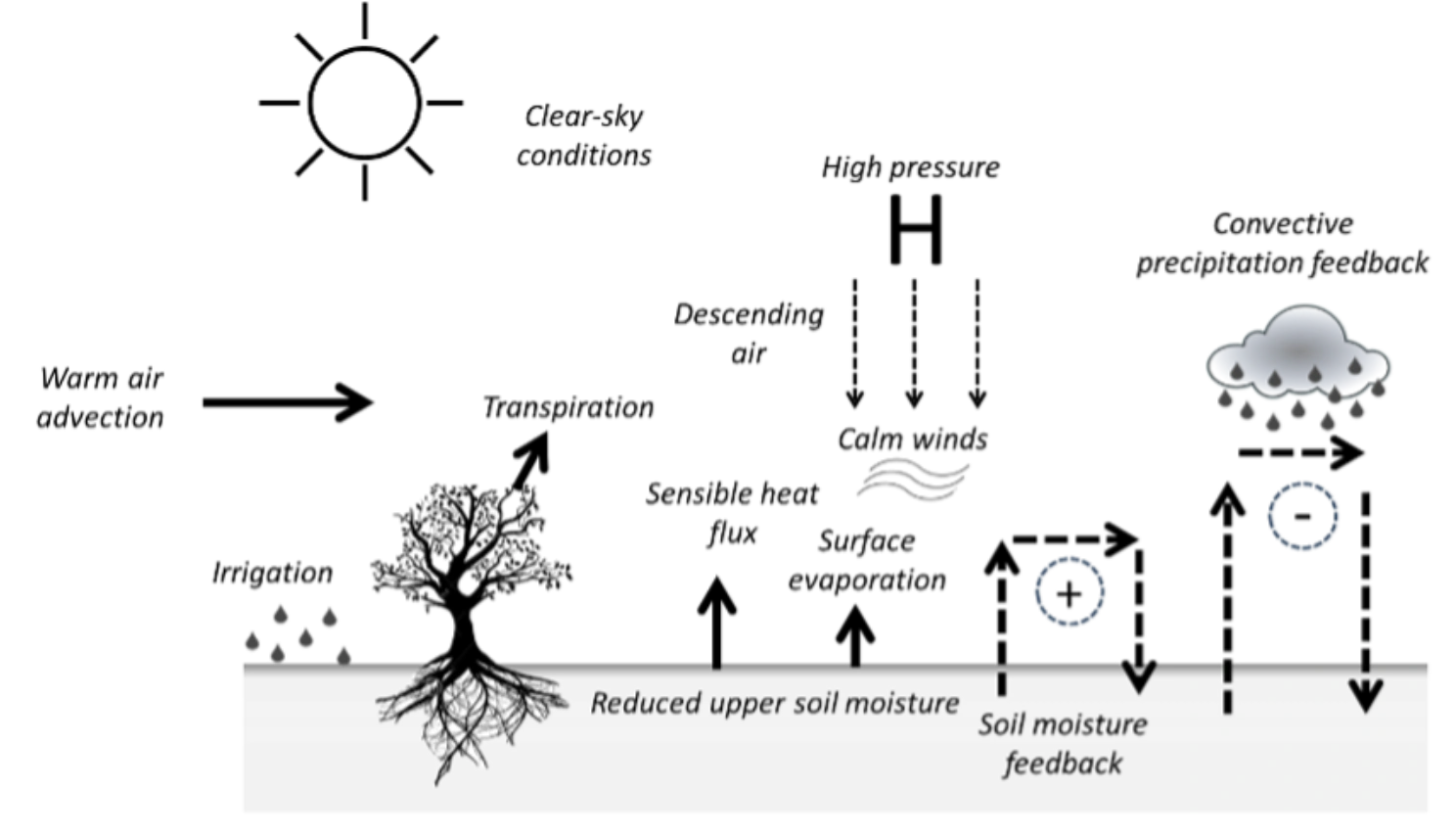

Schematic illustration of processes that can contribute to extremely high temperatures. Solid arrows represent driving mechanisms, while dashed arrows indicate potential feedbacks that may either amplify (+) or weaken (–) the heatwave.

How do heatwaves form on land?

Heatwaves on land arise from high‑pressure systems that develop during summer. These systems create clear skies, allowing the sun to intensely heat the ground. As the surface warms, water in the soil begins to evaporate. When moisture is present in the upper soil layers, some of the solar energy goes into evaporation rather than heating, which helps moderate temperatures.

This process works much like boiling water in a pot: as long as water is present, the pot cannot become extremely hot because liquid water never exceeds 100°C. Once the water evaporates completely, the pot itself begins to heat rapidly. Similarly, when the topsoil dries out, incoming solar energy goes directly into raising temperatures, intensifying the heatwave.

Vegetation also contributes to cooling through transpiration, where plants release moisture into the air. This is why heatwaves form more easily when soils are already dry or vegetation is sparse. Urban areas with large amounts of asphalt, buildings, and limited vegetation heat up particularly quickly due to the lack of moisture available for evaporation.

Persistent high‑pressure systems also cause air to sink. As sinking air is compressed, it warms further, adding another layer of heating near the ground and strengthening the heatwave.

How long does a heatwave last?

A heatwave continues for as long as the high‑pressure system remains in place—typically about one week, but severe events can last up to two. Once the high‑pressure system weakens or breaks down, the heatwave ends.

Interestingly, the conditions created by a heatwave can also help end it. As evaporation increases, moisture rises with warm air. Warm, moist air is buoyant, allowing it to ascend and form clouds. If enough moisture accumulates, these clouds can produce rain, which cools the surface and puts an end to the heatwave.

Impact of global warming

While the planet is warming, heatwaves are driven by persistent high‑pressure systems, and it is still uncertain how climate change will affect the frequency or persistence of these systems. Research is ongoing.

However, higher average temperatures do influence how intense heatwaves become. If an area warms by two degrees Celsius, heatwaves in that region may also become roughly two degrees hotter than they would have been in the past. Additionally, higher temperatures increase evaporation, drying soils and reducing their ability to moderate heatwaves. This creates a positive feedback loop, allowing heatwaves to intensify beyond what average warming alone would suggest.

Consequences of heatwaves

Even though heatwaves often last only about a week, they can have substantial effects on people, animals, ecosystems, and the economy.

Heat stress and heatstroke

The human body has a temperature “comfort zone” between 18°C and 30°C, where minimal energy is needed to regulate internal temperature. When temperatures rise beyond what the body can manage, heat stress can develop. Symptoms include excessive sweating, dizziness, fatigue, muscle cramps, and a rapid, weak pulse. Without cooling and hydration, heat stress can progress to heatstroke, a life‑threatening condition where sweating stops, confusion and nausea develop, and consciousness may be lost. Heatstroke requires emergency medical care. Because heat stress can develop quickly, even a short heatwave can increase mortality.

Effects on wildlife

All warm‑blooded animals must maintain a stable internal temperature. Extreme heat affects both wildlife and livestock. Livestock exposed to heat stress expend extra energy on cooling, increasing respiration, pulse, and body temperature. As a result, their appetite declines, reducing milk production and altering milk composition. Meat production also decreases due to slower growth, lower slaughter weights, and reduced meat quality.

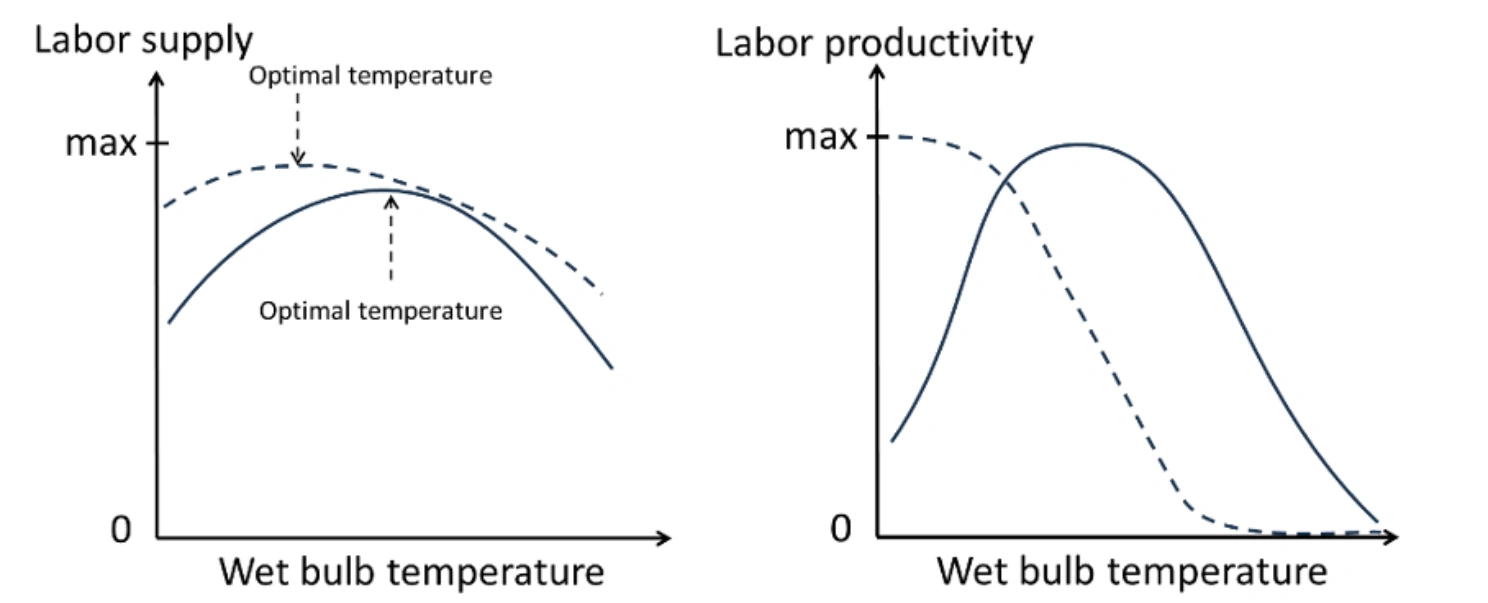

Schematic examples of how working hours and labor productivity may vary with heat stress (here expressed using the so‑called wet‑bulb globe temperature). Such curves will differ depending on the type of labor, the technologies used in the workplace, and the surrounding work culture. This is illustrated by the solid and dashed lines.

Economic consequences

Extreme temperatures reduce both available working hours and productivity. Outdoor sectors such as agriculture and construction are particularly affected, as workers must take more breaks or slow their pace to avoid heat stress.

Globally, about one in four paid workers works outdoors. According to the 2023 Lancet Countdown report, heat exposure caused the loss of 490 billion potential working hours in 2022, primarily in agriculture and construction. These losses disproportionately affect low‑income workers with limited protection.

Humid or dry heatwave?

The impact of a heatwave depends heavily on humidity. In humid conditions, sweat evaporates more slowly, making it harder for the body to cool itself. This means a temperature may feel significantly hotter in a humid climate than in a dry one.

To capture this effect, several “heat indices” combine temperature and humidity to estimate perceived heat. However, direct sunlight also increases stress, so more advanced measures include:

- Air temperature

- Wet‑bulb temperature

- Globe temperature

Together, these form the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), a widely used indicator of heat stress. Because WBGT requires specialized instruments, it is not measured everywhere.

Example of a map showing the heat index and Wet‑Bulb temperature in a region of the United States.

Examples of heatwaves on land

One of the most severe heatwaves in modern European history occurred in 2003, causing extensive health impacts across the continent. Combined with drought, it led to reduced grain production in parts of Southern Europe. More than 70,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of the extreme heat. One major reason for the devastation was Europe’s limited experience with extreme heat at the time—public awareness and protective measures were insufficient, leaving many unprepared for such extreme temperatures.

Referanser

Statement – Heat claims more than 175 000 lives annually in the WHO European Region, with numbers set to soar

Lancet Countdown

Dødstall for 2003 hetebølgen

Kontaktpersoner

Asgeir Sorteberg

Professor - Climate Hazards, UiB - University of Bergen